Decades-Old Mystery Solved

Technion scientist discovers the key to decades-old mystery surrounding structure insensibility - a previously unexplained phenomenon in catalysis

Catalysis is responsible for 95% of industrial chemical processes, and directly affects more than 1/3 of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP). What is catalysis? It is the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction; “helping it” – achieved by means of a catalyst – a “starter”. The catalyst is not consumed by the reaction, nor changed by it, and can keep on “helping” indefinitely (although in practice catalysts can deactivate in seconds to years). It can be likened to a bossy matchmaker, bringing couples together.

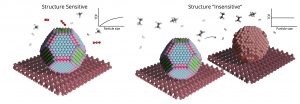

Operando spectroscopy, characterizing catalysts while they are working, forms the basis of the research in Vogt’s group

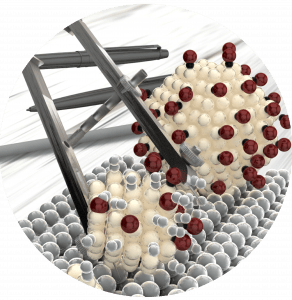

Many catalysts are made up of nanoparticles on a support, which can have varied structures. A smaller particle has more irregular surfaces, with peaks and valleys, and displays more atoms “sticking out”. A larger particle would have more flat areas. The nanoparticle’s shape and size should affect how effective they are at catalyzing a reaction, depending on whether the reaction needs the peaks and valleys or the flat surfaces. Except sometimes the shape appears to have absolutely no effect – no matter whether the particles are big or small, the reaction occurs at the same rate. This is called “structure insensitivity”. It is a phenomenon that is empirically observed, but for a long time it remained unexplained. It had already been theoretically accepted that it should not exist. Now, Prof. Charlotte Vogt from the Schulich Faculty of Chemistry at the Technion, together with an international team of scientists, has found the answer.

Some reactions are structure-sensitive (the surface-normalized catalytic activity changes with catalyst particle size) while others seem to be structure-insensitive (the surface-normalized catalytic activity does not change with catalyst particle size). Vogt and coworkers now explain why the latter is seen; the nanoparticles restructure exposing only certain specific sites.

Prof. Vogt used advanced characterization methods, including particle accelerators and quick spectroscopy to discover that the reactions indeed only appear to be structure insensitive. In truth, what happens is that the catalyst nanoparticle undergoes rapid restructuring. It changes its shape, and displays not the expected “flat surfaces”, but peaks and valleys, leaving only specific reactive sites exposed. The process is so fast, that without the novel technology, and smart experimental design, it could not have been observed.

The study was a collaboration between the Technion, Utrecht University, Eindhoven University, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Stony Brook University, and the Paul Scherrer Institute. It was recently published in Nature Communications.

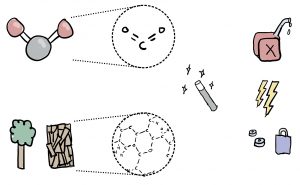

One of the big challenges society faces in this century is to make our fuels, materials, and chemicals from fossil-fuel alternatives, such as perhaps carbon dioxide, or biomass waste

Catalysis plays such an important role in nearly every industry; it is easy to see how understanding catalysts and improving them can have a significant impact. Prof. Vogt explains: “I believe the key to a greener, more sustainable future lies in better catalysts. Imagine, for example, turning CO2 into useful compounds. It sounds like science fiction. The truth is, such a process is theoretically possible, but it is not yet energy efficient. Right now, it would create more pollution than it would save. If, however we could lower the amount of energy required, or if we would be able to tune the catalyst to make specific products, if we could find catalysts that would make these things easier, suddenly it would become feasible. Remember, acid rain used to be a problem we talked about even two decades ago; and now we no longer do. It was solved, using catalysts.”

Prof. Vogt, aged 30, was born in the Netherlands. She arrived in Israel for her Ph.D., and to use her words, fell in love with the country. “This place is amazing,” she says. “I love the sun, the beaches, the food, the vibrant society. I love how open and warm people are. I was made to feel very welcome here. There’s another aspect too: you value family, but also a modern lifestyle; as a woman, I’m not expected here to choose between a career and a family – I can have both.”

As a scientist too, Prof. Vogt is happy. “There is a culture of search for knowledge here,” she says. “I love applied science, but in my view to truly make an impact, you have to base that on fundamental research. In Israel, that is appreciated, and also funded. I am grateful for bodies like the Israel Science Foundation, which fund research without immediately demanding practical goals. They allow scientists to “play around” with ideas and experiments and make new discoveries. These discoveries are the basis of break-through technological developments in time. It is the difference between going into a room with the purpose of finding a particular tool, and simply going into the same room to explore what’s there. In the first scenario, you’ll find the tool you’re looking for, and only that. In the second, you might find something so much better! That’s the difference between incremental improvements – which are also important – and true scientific breakthroughs.” Of the students in Israel she says, “they come to me with ideas – they don’t wait around to be told what to do.” And the infrastructure is also what she needs. “I used to have to fly from the Netherlands to the US to do some of my experiments,” she explains. “Now I’m going to have almost all the equipment I need next door, for example at the Sarah and Moshe Zisapel nanoelectronics center.”

In 2019, Prof. Vogt won the Israel Vacuum Society (IVS) award for “outstanding early-career achievements”. This year, she was included in the Forbes 30 under 30 Europe, and received the Clara Immerwahr Award – an award for promoting equity and excellence in catalysis research, fostering young female scientists at an early stage of their career. She opened the Catalysis for Fuels of the Future Laboratory at the Schulich Faculty of Chemistry and joined the Grand Technion Energy Program (GTEP) in March 2021. She now looks to study catalytic reactions in all the complexity involved in their real-life applications, elucidate the mechanism of varied reactions, and apply this knowledge to help to design new catalysts and better processes to abate climate change.