שמונה מוקדי מחקר בהובלת הטכניון זכו במענקי ות"ת בתחומי הקיימות ומשבר האקלים

המוקדים עוסקים במגוון תחומים ובהם אנרגיה, תזונה, מערכות מים, איכות מים ופרוטאומיקה.

המוקדים עוסקים במגוון תחומים ובהם אנרגיה, תזונה, מערכות מים, איכות מים ופרוטאומיקה.

פרופ' חוסאם חאיק, דיקן לימודי הסמכה וחבר סגל בפקולטה להנדסה כימית ע"ש וולפסון בטכניון, זכה בפרס הבין-לאומי היוקרתי המוענק על ידי אגודת מחקר החומרים

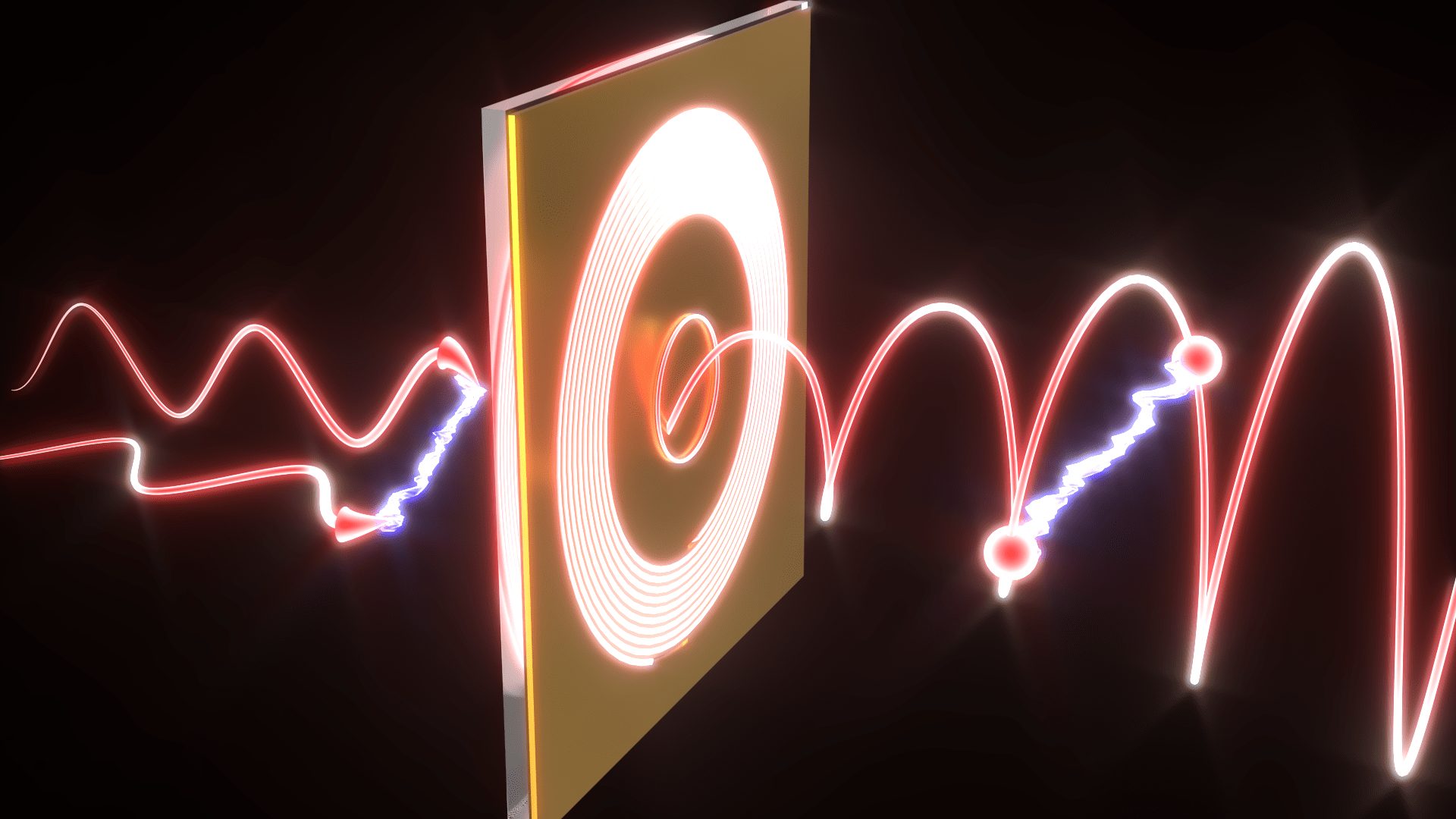

השזירות שהתגלתה מתקיימת בתנע הזוויתי הכולל של חלקיקי אור (פוטונים) הלכודים במבנים זעירים שגודלם כאלפית השערה. תגלית זו תתרום למזעור עתידי של רכיבים לתקשורת קוונטית ומחשוב קוונטי

מחברות סטארט-אפ ועד לקווי החזית, הבוגרים החדשים מגלמים את שילוב הערכים, העשייה והקדמה

טקס יום הזיכרון לחללי מערכות ישראל ופעולות איבה וטרור

29.04.2025 שלישי, בשעה 11:00

הוספה ליומן

מוסיקה, מדע והשראה - הסוד מאחורי השראה: מדענים ואמנים בשיחה פתוחה

07.05.2025 רביעי, בשעה 15:00

הוספה ליומן

יום יזמות, קריירה וחברה ויריד תעסוקה

13.05.2025 שלישי, בשעה 08:00

הוספה ליומן

פסטיבל הסטודנט המשותף בטכניון

21.05.2025 רביעי, בשעה 20:00

הוספה ליומן

100000

בוגרים

18

פקולטות

15000

סטודנטים

60

מרכזי מחקר

ברחבי הקמפוס