Category Archives: Uncategorized

Update from Technion

Monday, 15 April 2024, 18:00

Shalom,

In line with the latest directives from the Home Front Command and the lifting of restrictions on Israel’s education system, work, research, educational activities, and exams at Technion campuses will resume as normal tomorrow.

Instructions regarding examinations originally scheduled for Sunday and Monday, April 14-15, 2024, as well as solutions for schedule conflicts of exams, have been issued by the School of Undergraduate Studies.

We wish you success in your upcoming exams and hope for a peaceful week ahead.

Technion Update: Schedule Changes and Safety Measures

Date: Sunday, April 14, 2024, 19:45

Dear Technion Community,

In light of the recent directives from the Home Front Command, effective through Monday, April 15, 2024, at 23:00, we are issuing the following important updates:

- Examination Schedule: All exams scheduled for Monday, April 15, have also been postponed.

Exams originally set for today, Sunday, April 14, are rescheduled for Wednesday, April 17, 2024, at 5:00 PM.

Exams that were to be held on Monday, April 15, will now take place on Thursday, April 18, 2024, at 5:00 PM.

Updated room assignments will be available on the student portal tomorrow. Please note that certain subjects may have different rescheduled dates; those affected will receive direct notifications. Additionally, the Undergraduate Studies Office will provide alternative dates for any overlapping exams.

- Campus Operations:

Both Technion and TRDF staff at all campuses will work as usual tomorrow. Parents with children up to 14 years old may choose to work remotely. Managers are expected to accommodate this, and demonstrate flexibility in addressing the needs of their teams.

- Support Services:

The Dean of Students’ office is accessible 24/7 for student concerns. Students can reach the Center for Counseling and Support via phone at 077-8874112 or email at counseling-director@technion.ac.il during regular business hours. For immediate assistance, message us on WhatsApp at https://wa.me/message/MTWCFMOC3YN7B1.

The Human Resources Department is also available for urgent inquiries from administrative and academic staff at any time via WhatsApp at 053-5466258.

- Safety Precautions:

Please familiarize yourself with the locations of shelters and secure rooms on campus. Remain prepared by reviewing emergency procedures. Links to the list of shelters and an instructional video on emergency behavior are provided for your convenience:

Shelters and secure rooms: https://bit.ly/46HtZmi.

Emergency behavior video: https://bit.ly/3rJjDmR.

Stay safe and well-informed.

Approximately 5,000 potential students had arrived by midmorning at the Technion’s open day, with many more expected at the faculty reception area situated at the Churchill Auditorium Plaza. In the reception area, the various Technion faculties presented diverse study programs for undergraduate degrees in engineering and science, medicine, education, architecture, and urban planning. The open day included tours of the faculties and laboratories, lectures by Technion researchers, and an alumni panel.

This year saw a significant increase in the number of attendees. The Technion announced that participants in the event would receive a 50% discount on registration fees. A dedicated counseling station for reservists and their families provided information about the academic benefits that the Technion has established since the war to assist student reservists and make it easier for them to integrate into academic life. The station was operated by the Undergraduate Admissions Department.

The Dean of Student’s Office, which is responsible for assisting all Technion students with accommodation, scholarships, and welfare activities, also operated a special station. During this period, the Dean of Student’s Office has increased its activities in support of student reservists, and the Technion leads among Israeli academic institutions in the variety and scope of academic benefits, financial assistance, and emotional support provided to student reservists.

An alumni panel titled ‘The Technion gave me more,’ was held, where Technion alumni discussed how their studies at the Technion opened different career paths for them.

More than 500 students, faculty members, administrative staff, graduates, and guests participated today in the 8th Technion Race. The race took place in collaboration with the Technion administration, the Technion Student Association, and the Technion Sports Association. It opened with a minute of silence in memory of the fallen of operation “Swords of Iron” and with hope for the swift release of the hostages held by Hamas.

The race was started by the president of the Technion, Prof. Uri Sivan, and the vice chairperson of the Technion Student Association, Alis Kalman. The president stated that “in recent months, we have received clear evidence of our resilience as a community committed to mutual support, as students led by our Student Union, staff, and faculty have volunteered for a huge variety of activities for the benefit of the community and the country. The Technion Race is another opportunity for all of us to be together as one community. Good luck to everyone.”

Nitzan Yissar, coach of the Technion’s orienteering team and Israeli champion in orienteering, won overall first place with a time of 17:47:20. In the women’s category, Amal Hihy, a first-year student in the Taub Faculty of Computer Science won with a time of 21:27:01. Hihy, who lives in Hoshaya, dedicated her running career to the memory of her father, Faiz, who was killed before her birth. Years ago, in her first competitive race she won first place. She then joined the “Adrenaline” running group and now runs as part of the Maccabi Haifa team.

At the end of the race, medals were awarded by category, and in a lottery held among all participants. Amitai Ginsburg, a student in the Faculties of Materials Science and Physics received a prize of 1,000 shekels. Vice chairperson of the Technion Student Association, Alis Kalman, said: “Sport is something that unites us all – it has no color or gender – and it makes us all feel good.”

The grants are intended to prove feasibility and accelerate the translation of academic research projects into the application and commercialization phase, including founding start-up companies

Prof. Yoav Shechtman

Prof. Netanel Korin

Prof. Shahar Kvatinsky

Three Technion researchers were recently awarded advanced Proof of Concept grants from the European Research Council (ERC). Each researcher will receive €150,000, to be used for advancing the translation of their academic research into commercial applications, including founding start-up companies. These grants are only offered to researchers who have previously received ERC grants.

Associate Professor Shahar Kvatinsky of the Andrew and Erna Viterbi Faculty of Electrical and Computer Engineering will use his grant to build computers with much faster data processing capabilities. Thanks to an innovative computer architecture, the computing will take place in the computer’s memory rather than in the actual data processor. These innovative computers will be significantly faster than existing computers and will facilitate the management and analysis of intricate data sets in diverse sectors, such as finance, healthcare, and social media platforms.

Associate Professor Yoav Shechtman of the Faculty of Biomedical Engineering will use his grant to develop sensitive detection of protein concentrations using computational microscopy. The researchers developed a simple and fast way to measure concentrations of protein in samples of blood or other bodily fluids. The method is based on a microscope with the addition of an optical element designed in Prof. Shechtman’s laboratory. The system tracks fluorescent particles attached to the protein of interest through antibodies. The images are processed by a computer, and the protein concentration is extracted algorithmically. This new method is being studied to monitor protein in the immune system of cancer patients undergoing biological treatment, to enable early detection of side effects and, hopefully, provide preventive treatment. The research is being carried out in collaboration with the Rambam Health Care Campus.

Associate Professor Netanel Korin of the Faculty of Biomedical Engineering is using his grant to develop a solution aimed at preventing blood clots in prosthetic heart valves, a problem related to the abnormal flow in these valves. He was inspired by passive flow control phenomena observed in nature and applied in the aerodynamics industry. Following this principle, a slight modification in the physical structure of a fish fin, bird wing, or airplane wing can induce a significant change in flow characteristics, providing substantial benefits for swimming or flying. Similarly, Prof. Korin and his team aim to develop a novel artificial valve that utilizes passive flow control and redirects a portion of the blood flow to “wash” areas where blood clots are likely to accumulate. The research in Prof. Korin’s lab is led by Yevgeniy Kreinin as part of his doctoral research.

The Technion announced today that two well-known foundations have joined together in a collaborative effort to enhance the Technion Human Health Initiative. The undertaking will establish the D. Dan and Betty Kahn Human Health Building, which will be home to the Bruce and Ruth Rappaport Cancer Research Center.

[CONTINUED BELOW]

At the cornerstone laying ceremony

Nobel Laureate in Chemistry, Prof. Aaron Ciechanover

From left to right: Larry and Andi Wolfe, Irith Rappaport, Shir Goldstein and Technion President Prof. Uri Sivan

From left to right: Advocate Moriel Matalon, Larry and Andi Wolfe, Technion President Prof. Uri Sivan, Irith Rappaport, Glen Perry and Shir Goldstein.

Technion President Prof. Uri Sivan said, “The construction of this building and the cancer research center housed in it is nothing less than a historic event. We are celebrating today two of the largest donations in the history of the Technion, which were made possible thanks to a first of its kind partnership between two foundations that share a long-standing tradition of generously supporting the Technion: the D. Dan and Betty Kahn Foundation and The Bruce and Ruth Rappaport Foundation.”

“I lack the words to fully describe our gratitude to these two foundations and to those who worked tirelessly to bring the dream to life,” continued President Sivan. “The goals of the gift, reflected in the titles of the building and the research center, are cancer research and human health, using a multidisciplinary approach and relying on all the Technion’s capabilities and its close ties with hospitals, in particular with the Rambam Healthcare Campus. I find it symbolic that these donations are made on the golden jubilee of the Technion Faculty of Medicine, and at the opening of the Technion Centennial year. The generosity and the vision of the donors reflected in this initiative will lead the Technion to new heights. We will advance into the second century of the Technion, able to improve the lives of millions of people in Israel and around the world.”

The cornerstone laying ceremony was held during the Technion’s Board of Governors meeting in June at the Ruth and Bruce Rappaport Faculty of Medicine. Participants included philanthropists Ms. Irith Rappaport and Andi and Larry Wolfe; Technion President Prof. Uri Sivan; Dean of the Ruth and Bruce Rappaport Faculty of Medicine Prof. Ami Aronheim; Nobel Laureate and Distinguished Prof. Aaron Ciechanover, who will be the Chairman of the Board of Directors of the new Cancer Research Center; Prof. Amir Orian, head of the Cancer Research Center; members of the Technion senior administration and Board of Governors; faculty members; and representatives of Technion Societies around the world.

Nobel Laureate Distinguished Professor Aaron Ciechanover, who conceived and established the center, recalled a line from the Mishnah that Bruce Rappaport used to quote: “without flour there is no Torah, but with no Torah there is no flour.” “This wisdom accompanied Bruce for decades. The Technion provided the Torah, the learning, he’d say, while the Rappaport family provided the flour.”

“I started to dream about this Center when the first cancer drug based on the ubiquitin mechanism, which Professor Hershko and I discovered, came to the market,” he continued. “When you start basic research, you never know where it’s going to lead you. We, the researchers, are committed to turn this Center into a world leader research center.”

Ruth and Bruce Rappaport, may their memory be a blessing, were two of the greatest friends of the Technion and among the generous philanthropists whose donations assisted in erecting the Ruth and Bruce Rappaport Faculty of Medicine building and the Rappaport Family Institute for Research in the Medical Sciences. The faculty building was inaugurated in 1979. Even then, the Rappaports believed faculty members would come to win the Nobel Prize; a prophecy that came true when Distinguished Professors Avram Hershko and Aaron Ciechanover were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2004. In addition to raising the Ruth and Bruce Rappaport Faculty of Medicine and the Rappaport Family Institute for Research in the Medical Sciences, Ruth and Bruce Rappaport, together with the Rambam Health Care Campus, initiated the construction of the Ruth Rappaport Children’s Hospital.

Ruth and Bruce Rappaport were Technion Guardians; a title reserved for those who made among the highest level of commitments to the Technion. In 2014, the Technion awarded Ruth Rappaport an honorary doctorate. She passed away in 2018, eight years after her husband Bruce. Their philanthropic legacy is continued by their daughters Ms. Irith Rappaport and Dr. Vered Drenger. In appreciation of her outstanding contribution to the Technion and to other philanthropic causes, the Technion awarded Ms. Irith Rappaport an honorary doctorate in 2022.

“I would like to dedicate this day and moment to my late sister Shoshana, who passed away last July after relentlessly fighting cancer for 7 years,” Ms. Irith Rappaport spoke at the ceremony. “Despite the best available doctors, medications and innovative treatments that helped delay the bitter end, eventually the disease won. I’m sure that most of you have experienced such painful losses. Unfortunately, millions around the world are facing the same fate as we speak, and therefore it is clear to me that there is still a long way to go and a lot of research to be done in developing a comprehensive solution to this cursed disease. My parents, who were true guardians of this academic institution, would undoubtedly be delighted to see their vision and values transformed into reality with the same passion and excitement they always had in their philanthropy. Because at the end of the day, philanthropy is about passion and people. I can only hope that the research that will be carried out in the new Center will keep pushing the boundaries of innovation for the betterment of mankind.”

Dan and Betty Kahn, of blessed memory, were among the Technion’s most important benefactors and Technion Guardians. The bond between Dan and Betty Kahn and the Technion was forged in the early 1960s, and in 2008 their foundation constructed the D. Dan and Betty Kahn School of Mechanical Engineering. Dan and Betty Kahn were among the original contributors to the first building of the Faculty of Aerospace Engineering. Dan Kahn was a member of the Technion Board of Governors and the American Technion Society (ATS) Board of Directors and served as the president of ATS – Detroit. The Technion awarded him an Honorary Fellowship in 2006, and in 2011 bestowed upon him an Honorary Doctorate. The legacy of Dan and Betty Kahn is continued today by their daughter Andrea (Andi) together with her husband Larry Wolfe. Larry embraced philanthropy following Dan Kahn’s example, deepening his involvement with the Jewish community in Detroit, the U.S., and Israel. In 2012 he was named president of the D. Dan and Betty Kahn Foundation. In this capacity, he is involved in the Michigan-Israel Partnership for Research and Education, in which the Technion plays a major role. Andi Wolfe is active on multiple boards involving Jewish communities in Israel and the USA. She has been a member of the local and National Boards of Directors of the ATS for many years and is a member of the Technion Board of Governors. Last year, Andi and Larry Wolfe established the Wolfe Center for Translational Medicine and Engineering in the Helmsley Health Discovery Tower; a collaboration between the Technion and Rambam Healthcare Campus. The Wolfe Center serves as a platform for in-depth applicative clinical research.

“On behalf of the D. Dan and Betty Kahn Foundation and my fellow Trustees, Patti Aaron and Arthur Weiss, I would like to thank President Uri Sivan for his vision of undertaking the Technion Human Health Initiative, Professor Aaron Ciechanover for his leadership and most importantly the Rappaport Foundation for its participation is this ambitious project,” said Larry Wolfe, President of the Khan Foundation.

Prof. Ami Aronheim, Dean of the Ruth and Bruce Rappaport Faculty of Medicine said, “It is a symbolic event. Here will be combined the engineering strength of the Technion and the clinical strength of the affiliated hospital. The faculty and the hospital will become a leading player in cancer research, a research hub for innovation. The Center will enable us to conduct cutting-edge research that would serve as a catalyst for developing life-saving treatments. Your support and endless generosity have made this dream come true.”

For photos click here

- From left to right: Larry and Andi Wolfe, Irith Rappaport, Shir Goldstein and Technion President Prof. Uri Sivan

- From left to right: Advocate Moriel Matalon, Larry and Andi Wolfe, Technion President Prof. Uri Sivan, Irith Rappaport, Glen Perry and Shir Goldstein.

- Nobel Laureate Distinguished Professor Aaron Ciechanover

Photos: Rami Shelush for the Technion’s spokeswoman’s office

For more information: Doron Shaham, Technion Spokesperson, +972-50-3109088

On Sunday, the Technion halted all activities and held a rally in solidarity with the hostages being held in captivity by Hamas

Hundreds of students and administrative and academic staff members took part in a rally to mark 100 days since the events of October 7th and to identify with the children, women, men, and elderly still being held hostage in the Gaza Strip. At 11 o’clock on Sunday, January 14th, the Technion suspended all teaching, research and other activities in solidarity with the hostages and their families.

[CONTINUED BELOW]

Carmit Palty Katzir

Itay Israel

Prof. Adi Salzberg

Adi Kikozashvili

Students with yellow balloons

Students at the Technion rally

The rally, which was organized by the Technion Student Association together with the Technion, included speeches by Prof. Adi Salzberg, Vice President for Diversity and Inclusion; Itay Israel, Chair of the Technion Student Association; and family members of hostages: Carmit Palty Katzir from Kibbutz Nir Oz, (the wife of Prof. Raz Palty of the Rappaport Faculty of Medicine), whose brother Elad Katzir is a hostage in Gaza; and Adi Kikozashvili, a student in the Faculty of Biotechnology and Food Engineering whose brother Shlomi Ziv is being held captive in Gaza.

“Today, January 14th, 2024, is the first day of the new academic year at the Technion. It is the 100th time that we are opening a new academic year,” Prof. Adi Salzberg said at the rally. “The first day of a new academic year is usually a festive and happy occasion, but today we are unable to feel joy because this day marks exactly 100 days since the horrendous massacre carried out by the Hamas terrorists on October 7th; 100 days since the cruel kidnapping of hundreds of women, men, children and elderly to the Gaza Strip, which is contrary to every moral principle and certainly to international law. Each and every hostage is an entire world. We must not despair, we must not give up until every last hostage returns home safely, and their families will be able to breathe once again.”

“100 days is such a long amount of time,” said Itay Israel at the rally. “That’s 100 days during which they weren’t at home, where they ought to be. We must do everything possible for their return. This should be the first and the only priority. One hundred days in captivity is 100 days too many.”

Carmit Palty Katzir, whose mother Hanna Katzir was released from Hamas captivity but whose brother Elad is still in Gaza, said: “Unfortunately, the stories told by those who returned from captivity revealed to us how life as a hostage of Hamas looks and feels, including starvation, physical and psychological violence, abuse and severe medical neglect.

We must not be indifferent to their suffering. Each of us should see ourselves as if we are hostages in Gaza. They need us to cry out for them. Each day in captivity has an enormous price, whose significance is life or death. This is an emergency, and we are being tested as a society and a country. It is our moral duty to ensure that they return home today. It is the State’s basic duty to protect its citizens and to act with determination to bring them home alive. We must not get used to the idea that they are there, wounded in enemy territory, and we are here. The struggle to release the hostages must not become ‘business as usual.’”

“It has already been 100 days during each of which they again experience the hell of October 7th,” she continued. “The difference between them and us is that we are here, protected against the rain, violence and hunger – free, while they are there, in a physical and psychological abyss, in the grip of monsters, experiencing never-ending terror. Israeli society will not heal and recover until they come back to us.”

Adi Kikozashvili, whose brother Shlomi was kidnapped to Gaza from the Nova music festival where he worked as part of the security detail, said: “On the morning of Simhat Torah, October 7th, on that horrible morning when Israel suffered a terrible blow, my brother was taken hostage. Shlomi is my big brother, the oldest sibling. He is the first to give me advice, to comfort me, the first to be there when needed, and I miss him so much. Next week, he will celebrate his 41st birthday. I wish that we will celebrate with him at home! Please spread unconditional love and reduce the amount of gratuitous hatred, pay attention to the friend sitting next to you in class, look people in the eye, see what is good in them, support one another, hug one another. I ask myself how it will be possible to return to my studies in these circumstances and the truth is that I have no idea. But we will do it with all the help and support that the Technion is giving us. We will succeed.”

Click here for pictures

- Carmit Palty Katzir

- Adi Kikozashvili

- Adi Salzberg, Vice President for Diversity and Inclusion

- Itay Israel, Chair of the Technion Student Association

- Students with yellow balloons in solidarity with the hostages

- Students at the Technion rally

Photos: Rami Shlush, Technion Spokesperson’s Office

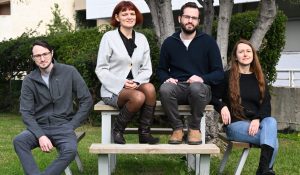

Professor Avner Rothschild’s research group at the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology developed a new green technology for producing hydrogen

Professor Avner Rothschild

From right to left: Dr. Anna Breytus, Matan Sananis, Dr. Yelena Davidova and Ilya Slobodkin

A group of researchers from the Technion Faculty of Materials Science and Engineering is presenting a new technology for producing green hydrogen using renewable energy. Their breakthrough was recently published in Nature Materials. The novel technology embodies significant advantages compared to other processes for producing green hydrogen, and its development into a commercial technology is likely to reduce the costs and accelerate the use of green hydrogen as a clean, sustainable alternative to fossil fuels.

Using hydrogen as a fuel instead of coal, gasoline, and “natural” gas will reduce the use of these fuels and greenhouse gas emissions from various sources, including transportation, the production of materials and chemicals, and industrial heating. Unlike these fuels, which emit carbon dioxide into the atmosphere when they combust in the air, using hydrogen produces water and is therefore considered a clean fuel.

However, the most common way to produce hydrogen involves using natural gas (or coal) and the process emits large amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere – thereby canceling out its advantages as a green, sustainable alternative for fossil fuels. In 2022, global consumption of hydrogen stood at approximately 95 million tons – a quantity suitable for improving various fuel products, and especially to produce ammonia, which is needed for manufacturing agricultural fertilizers. Nearly all of the hydrogen that is consumed today is produced from fossil fuels, which is why it is called “gray hydrogen” (made from methane) or “black hydrogen” (made from coal). Hydrogen production using these methods is responsible for around 2.5% of the annual global carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere as a result of human actions. Replacing gray hydrogen with green hydrogen is necessary in order to reduce this significant source of emissions and replace polluting fossil fuels with clean, sustainable hydrogen.

Various estimates predict that green hydrogen is likely to account for around 10% of the global energy market at net zero emissions – the current target for mitigating climate change and global warming as a result of the greenhouse effect due to increased concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. That is the reason for the enormous importance of green hydrogen in combatting global warming.

Green hydrogen is produced through electrolysis – electrochemical decomposition of water into oxygen and hydrogen using energy from renewable sources such as wind and sun. Electrolysis was discovered more than 200 years ago, and since then it has undergone many developments and improvements. However, it is still too expensive for producing green hydrogen at a competitive price. One of the technological challenges that limit the use of electrolysis for producing large amounts of green hydrogen – amounts that would help achieve plans to attain net zero carbon emissions – is the need for expensive membranes, gaskets and sealing components to separate the cathodic and anodic compartments.

Several years ago, Technion researchers presented an innovative and efficient electrolysis technique that doesn’t require a membrane and sealing to separate the two parts of the cell, since the hydrogen and the oxygen are produced at different stages of the process, unlike in regular electrolysis where they are created simultaneously. This novel process, called E-TAC, was developed by Dr. Hen Dotan and Dr. Avigail Landman under the supervision of Prof. Avner Rothschild and Prof. Gideon Grader. They partnered with the entrepreneur Talmon Marco to fulfill the process’s potential and develop commercial applications.

Details of the new technology

The researchers from Prof. Rothschild’s group at the Technion are now presenting a new process whereby hydrogen and oxygen are produced simultaneously in two separate cells, unlike the E-TAC process where they are produced in the same cell but at different stages. The new process was developed by Ilia Slobodkin as part of his master’s thesis, with the help of Senior Researcher Dr. Elena Davydova and Dr. Anna Breytus and master’s student Matan Sananis.

This novel process bypasses operational challenges and limitations of the solid electrode where the oxygen is produced in the E-TAC technique by replacing it with NaBr aqueous electrolyte in water. This replacement paves the way for a continuous process (as opposed to a batch process with E-TAC) and repeals the need to swing cold and hot electrolytes alternately through the cell. The bromide anions in the electrolyte are oxidized to bromate while producing hydrogen in a cathode, and they then flow with the aqueous electrolyte to a different cell, where they are turned back into their original state while at the same time producing oxygen, and this process keeps repeating itself. In this way, hydrogen and oxygen are produced at the same time in two separate cells in a continuous process without any temperature changes, unlike with E-TAC. Moreover, the oxygen is produced in the aqueous electrolyte and not in the solid electrode as in E-TAC, and it is therefore not dependent on the rate and capacity limitations typical of those types of electrodes, such as chargeable batteries.

In the article published in Nature Materials, the researchers describe their basic experiments which prove the preliminary feasibility of the proposed process, and present results that demonstrate its high efficiency and ability to work at high electric current, meaning that hydrogen can be produced at a high rate. At the same time, there is still a long way ahead for developing a new technology based on the scientific breakthrough depicted in the article. Such a technology is likely to get past the many obstacles on the way to industrial production of green hydrogen as a sustainable alternative to fossil fuels.

Prof. Rothschild is a member of the Nancy and Stephen Grand Technion Energy Program, the Stewart and Lynda Resnick Sustainability Center for Catalysis, and the National Research Institute for Energy Storage. The research was supported by the Ministry of Innovation, Science and Technology and JNF-KKL’s Climate Solution Prize.

Click here for the paper in Nature Materials

Click here for photos

Captions:

- (L-R) Ilia Slobodkin, Dr. Elena Davydova, Matan Sananis and Dr. Anna Breytus

- Avner Rothschild

Credit: Rami Shelush, Technion Spokesperson’s office

For more information: Doron Shaham, Technion spokesperson – 050-3109088

The Technion opens the new academic year with unprecedented support systems for reservists and for all students.

President of the Technion: “Opening the academic year is our response to attempts to undermine our lives.” More than 15,000 students will study at the Technion this year. The academic year was delayed out of consideration for students serving in the reserves.

The Technion will kick off the new academic year on Sunday, January 14, 2024, with 2,070 new undergraduate students, 48% of whom are women, and 1,029 new students pursuing advanced degrees, 40% of whom are women. The overall student body will total 15,000 students this year, including 10,745 undergraduate students, around 3,000 graduate students and 1,400 doctoral students. The youngest are not yet 18 years old, and the oldest is 76.

As in past years, the Faculties with the largest number of new undergraduate students are those relevant to high-tech professions: the Viterbi Faculty of Electrical and Computer Engineering, the Taub Faculty of Computer Science, and the Faculty of Data and Decision Sciences. The Faculty of Civil and Environmental Engineering is also one of the large Faculties for which there is high demand.

This year, there are more scholarships for research students pursuing advanced degrees, and the number of international students continues to grow steadily. Despite concerns about the difficult security situation in Israel, students from 11 different countries are beginning their studies at the Technion. They come from England, Argentina, the U.S., Ethiopia, India, China, Mexico, the Philippines, Canada, Russia, and Turkey. Eighty advanced-degree students will begin studying at the Jacobs Technion–Cornell Institute in New York and 17 new students will begin studying at the Guangdong Technion–Israel Institute of Technology in China.

“Together with the entire country, the Technion suffered a terrible and painful blow,” said Prof. Uri Sivan, president of the Technion. “Dozens of our community’s family members were murdered on October 7th and others were taken hostage. Many were wounded or killed in battle, and we are distraught and deeply pained.” The President explained that “we are opening the academic year because that has always been and remains our response to every attempt to disrupt our lives. We will continue to educate our students with the values that guided us during the last 100 turbulent years: tolerance, inclusion, and a commitment to truth and justice. We will continue to support the security and economy of the State of Israel, and no less importantly, we will continue to be committed to Israeli society out of a deep social responsibility towards all its citizens. The Technion has a long tradition of coexistence among all the communities on campus and we are determined to preserve this way of life. We are facing significant challenges, but based on my familiarity with the strength and resilience of the Technion family, I have no doubt that we will successfully overcome these challenges.”

Technion Senior Executive Vice President Prof. Oded Rabinovitch said, “We have been waiting a long time for students to return to the campus, and the opening of the new academic year is an opportunity for all of us to step up and do whatever we can to help the students adjust. This is a chance for us to pitch in to help those returning from the reserves, as well as those who will continue to serve during the semester and, indeed, all the Technion’s students. We foresee that there will be students who will continue to serve in the reserves after classes begin, and we will support them and make sure that they successfully complete their studies.”

The “Back on Track” program, which the Technion ran for the first time because of the war and its effects, took place during the last two weeks under the leadership of the Dean of Students Office and the Technion Students Association. The program included stress-relieving, recreational workshops and activities prior to returning to the classroom. This unique initiative helped students, especially those who served in the reserves, return to their studies as smoothly as possible, to take a break from the pressure and catch up.

Dean of Students Prof. Ayelet Fishman said, “We are proud of our reservists, and this pride is expressed through an array of steps that we are taking on their behalf. Our students who serve in the reserves do not only deserve our appreciation; they also deserve extensive help upon returning to their studies. Therefore, we have announced a series of academic adjustments and accommodations designed to help them, as well as a significant NIS 6,000 grant to be applied towards payments connected to their studies. These students will be exempt from paying rent on their campus dorm rooms, and they will receive emotional support as well as exemptions from certain exams from last year, among other steps. Like the rest of the country, the relationship between Jews and Arabs has been shaken by the war. As a result, we invested considerable resources to prepare for the students’ return to campus and the rehabilitation of our lives together. We have trained members of our faculty to teach mixed classes, and we have provided preparatory workshops for the dorm staff, as well as joint discussion groups and training for our student mentors – older students who serve as ‘big brothers and sisters’ to new students. We also established a Resilience Center and a telephone hotline to provide emotional and psychological help in Hebrew and Arabic. The entire student support and guidance team, which is part of the broad support network offered by the Office of the Dean of Students, received special training in preliminary therapeutic skills for helping trauma victims, and will operate according to the ‘trauma-aware campus’ model by adapting learning processes and helping ensure academic success.”

January 3, 2024

Dear Technion Family,

The academic year 5784 will commence soon and it will be a different and sorrowful year. The three months that have passed since October 7 have been painful and challenging for the State of Israel and the Technion family. Dozens of our friends’ family members were murdered, and others were abducted. Many have been injured or killed in the war, and our hearts are filled with pain and worry.

Approximately 2,500 students, faculty members, and administrative staff were called up for reserve duty, and many of them are still serving. In the spirit of Technion tradition, we postponed the opening of the academic year to await their return. As the expected release is delayed, we responded to the IDF’s request and delayed the opening of the year to January 14, 2024.

The upcoming academic year marks a historic milestone for us. Exactly one hundred years have passed since the Technion opened its doors in the historical building in Hadar HaCarmel with 16 male students and one female student. Who could have then foreseen that from that humble beginning would grow a top-tier research university, graduating one hundred thousand alumni, who have shouldered the security and prosperity of the State of Israel? Who could have imagined that our researchers would be awarded Nobel Prizes, and our influence on humanity would be so significant?

We did it all in our humble and persistent way, year after year. This has been our response to all the events, wars, and acts of terror that have afflicted us before the founding of the State and afterwards. This will also be our response to the appalling terrorist acts of Hamas, intended to undermine our determination, sow fear, create conflict within Israeli society, and drag us into the moral abyss in which they operate.

Nobody can divert us from our path. We will conquer the anger and the pain and immerse ourselves in achieving our goals with the spirit of our constitution: ‘To disseminate knowledge through education and promote knowledge through pure and applied research.’ We will continue to educate for the values that have guided us through the past tumultuous one hundred years: tolerance, inclusivity, the pursuit of truth and justice, and deep social responsibility towards all people. We will continue to support the security and economy of the State of Israel, and just as importantly, we will continue to embrace the entire Israeli society.

If we needed proof of our solidarity as a committed community, we received it in the last few months in the inspiring voluntary efforts of the Technion community. Alongside the enlistment of thousands in the reserves, the student union, academic and administrative staff rallied for a vast array of activities to support those whose lives were put on hold. We hosted hundreds of families who were evacuated from the south and north on campus, supported thousands of our own recruits, and addressed the diverse needs of the security forces.

This is the finest hour of the Technion family, and now we must channel these tremendous forces also to confront the additional challenges ahead of us. We must return to the routine of studies and research as in every year, and at the same time continue to support those among us whose lives have changed forever. We all must strive to heal the rifts in Israeli society, and we must continue to assist the thousands of women and men among us who left everything behind and enlisted to defend the country. We face enormous challenges, but from my acquaintance with this remarkable institution, its resilience, and the solidarity of the Technion family, I have no doubt that we will succeed.

Finally, I would like to remind you all, that my door and the doors of the entire administration are always open, especially during these challenging times. Please, do not hesitate to reach out with any problem or suggestion.

Wishing you all success and a fruitful academic year!

Prof. Uri Sivan

President

ACCESS PDF HERE: